Nuove tensioni tra Mar Rosso e Corno d’Africa (AGGIORNATO)

The article is also available in English at the bottom of the page

Dopo quasi due decadi di amnesie, lo scorso 12 dicembre, in occasione del 23° anniversario degli accordi di Algeri, il Dipartimento di Stato americano ha vergato un comunicato di 6 righe per ribadire l’importanza di rispettare i confini Etiopia – Eritrea. Una nota “curiosa” visto che l’Etiopia non li aveva rispettati per ben 18 anni e durante questo lungo periodo gli USA non hanno mai avuto nulla da eccepire.

Apparentemente un segnale di apertura all’Eritrea ce da tempo orami immemore è uno dei target preferiti delle “preoccupazioni umanitarie” nonché delle sanzioni americane. Al contempo un monito al premier etiope Abiy Ahmed che con le ultime sortite sul diritto dell’Etiopia ad avere uno sbocco sul Mar Rosso, ha mandato in fibrillazione i paesi costieri, a partire dall’Eritrea.

Per l’amministrazione di Joe Biden non è una conversione sulla via di Damasco, né un semplice omaggio di rito come conferma il repentino copia-incolla della segreteria dell’alto rappresentate UE per gli affari esteri Joseph Borrell. L’attuale politica estera americana si inserisce nel solco delle precedenti amministrazioni che hanno sempre silenziosamente appoggiato l’occupazione etiope dei confini eritrei nell’area di Badme. Una totale inosservanza degli accordi di Algeri del 2000 e delle direttive della Ethiopian Boundary Commission delle Nazioni Unite portata avanti nel disinteresse generale della comunità internazionale e conclusasi solo nel 2018 con l’arrivo di Abiy Ahmed che ritirò le truppe etiopi dall’area e distese i rapporti con l’Eritrea “guadagnandosi” il Nobel per la Pace.

Evidentemente, ci volevano gli Houti, i ribelli sciiti dello Yemen che da settimane minacciano le navi sul Mar Rosso, per spingere gli americani a rivedere la propria strategia africana. Del resto lo stretto di Bab el Mandeb è canale di estremo interesse, qui vi scorre il 12% del commercio mondiale, il 10% del petrolio consegnato via mare e l’8% del gas liquido (Gnl). Sempre da qui passano i rifornimenti a Israele e l’allargamento di un fronte meridionale del conflitto a Gaza fa emergere in tutta la sua problematicità il sempre maggiore isolamento nell’area sia di Israele sia degli USA che vedono i propri storici alleati come Egitto e Arabia Saudita sempre più vicini alla sfera d’influenza cinese e ai BRICS.

In questo scenario, una escalation nel Medio Oriente, oltre a destabilizzare la penisola arabica, potrebbe essere un’ottima occasione per far saltare l’accordo di pace sciiti-sunniti mediato dalla Cina, ricondurre i sauditi sotto l’influenza di Washington e così rilanciare gli accordi di Abramo.

Non è infatti un mistero che l’indebolimento del BRICS e dei suoi due paesi fondamentali (Russia e Cina) siano visti dagli USA come l’elemento fondamentale della propria politica estera e in questa ottica un coinvolgimento dell’Eritrea potrebbe certo fare comodo, a partire dall’operazione navale di polizia internazionale Prosperity Guard (OPG) per proteggere i mercantili in transito dagli attacchi degli Houthi. Inoltre, oltre ad essere snodo centrale della Via della Seta, con i suoi 1,251 chilometri di costa sul Mar Rosso, l’Eritrea è prima dirimpettaia dello Yemen e, grazie ai suoi ottimi rapporti con Arabia Saudita, Egitto e Sudan, potrebbe rivelarsi cruciale per gli equilibri dell’area.

Di contro, l’Etiopia, storico avamposto USA nell’Africa orientale, si sta rivelando un Paese il cui attuale assetto politico non sembra convincere del tutto Washington, disinteressata come sembra a salvarla dal baratro economico, a partire da quei 3,5 miliardi di dollari del Fondo Monetario Internazionale e altrettanti della Banca Mondiale cui l’Etiopia è ancora appesa. Con un’inflazione al 30% e grave mancanza di valuta estera, l’Etiopia sta affrontando una congiuntura economica difficilissima tant’è che dopo il mancato pagamento di una cedola da 33 milioni di dollari su una obbligazione da 1 miliardo di dollari emessa nel 2014, è ormai ufficialmente in default. Il terzo Paese africano dopo Zambia e Ghana a finire in insolvenza sul debito estero.

Etiopia-USA: liaison ritrovata, per poco…

Solo fino a qualche mese fa, tutto faceva pensare che Etiopia e Stati Uniti avessero ritrovato la liaison d’un tempo, quella costruita durante i 27 anni in cui il TPLF (Fronte popolare di liberazione del Tigray) era al potere e in cui aveva trasformato l’Etiopia in una sorta di stato satellite di Washington, un avamposto prezioso in una zona strategica come il Corno d’Africa.

Complicità che si era interrotta nel 2018 quando le prime mosse di Abiy Ahmed suggerivano un nuovo corso di netta rottura con la linea americana. Non solo per la decisione di distendere i rapporti con l’Eritrea, in contrasto con la politica USA che accusava Asmara di supportare i terroristi somali di Al Shabaab salvo poi ammettere di non aver mai avuto prove, ma anche per l’iniziativa di realizzare la Diga della Rinascita (GERD) sul Nilo Azzurro, anche qui in piena rottura con gli USA che si sono sempre allineati con le preoccupazioni del Cairo sulla gestione delle acque.

L’intenzione di anteporre gli interessi nazionali alle pressioni oltreoceano, Abiy l’aveva mostrata anche durante la guerra in Tigray. Una crisi innescata dal TPLF il 4 novembre 2020 contro il governo etiope ma che era stata raccontata al mondo come un genocidio portato avanti da Abiy Ahmed ai danni dell’etnia tigrina. Non c’era invece nessun genocidio, nessun blocco agli aiuti come testimoniato dai dirigenti del World Food Program i cui convogli hanno raggiunto 3 milioni di persone solo nel 2022.

C’era invece una guerra di secessione scatenata dal gruppo armato tigrino contro l’esercito federale e le regioni limitrofe Amhara e Afar, sfociata in una serie di crimini di guerra commessi da entrambe le parti ma pagate in primis dall’Etiopia prontamente sanzionata dagli USA con la sospensione dalle facilitazioni all’export previste dall’Agoa (African Growth and Opportunity Act) per “motivi umanitari”. Facilitazioni che avevano permesso all’export etiope verso gli USA di crescere oltre il 50% in un anno ma che una volta sospese hanno causato la perdita di almeno 100 mila posti di lavoro.

Poi qualcosa è cambiato. E’ cambiato Abiy Ahmed (il consenso è in caduta libera) e dopo la recente guerra in Tigray sono cambiati gli atteggiamenti della comunità internazionale nei confronti dell’Etiopia (“curiosamente” in meglio). Un cambio di rotta che ha il suo punto di svolta nella pace che il governo etiope ha firmato a Pretoria il 2 novembre 2022 e che concluse il conflitto con un bilancio di un milione di morti e una spesa per il Paese pari a 25 miliardi di dollari.

Un danno enorme che era valso al TPLF la dicitura di “gruppo terrorista” da parte del parlamento etiope. Etichetta che, come da accordi di pace, viene fatta scomparire. Non tutti i punti dell’accordo sono stati però rispettati a partire da quello che prevedeva il completo disarmo del TPLF che ad oggi, nonostante le divisioni interne, è ancora militarmente in forze e può contare su 200 mila uomini armati. Anche i leader tigrini sono ancora ben saldi al loro posto. Dai leader del TPLF Debretsion Gebremichael all’ex portavoce Getachew Reda che guida il governo ad interim del Tigray e non disdegna strette di mano con il premier etiope Abiy Ahmed che solo 12 mesi prima definiva “leader genocida e sanguinario”.

Un graduale avvicinamento al TPLF da parte del premier etiope vissuto come un vero e proprio tradimento dalla quasi totalità del Paese che è ancora memore di come la vecchia leadership si fosse macchiata di sanguinose repressioni delle proteste delle popolazioni Oromo ed Amhara nel 2015 e 2016 fino alla guerra d’aggressione contro l’Eritrea tra il 1998 e il 2000.

Un senso di tradimento pervade anche quanti avevano dato vita a #nomore, il movimento di orgoglio africano che durante il conflitto in Tigray aveva eletto Abiy a simbolo di una resistenza contro le ingerenze occidentali. In quel momento l’Etiopia era vittima di una pesante campagna mediatica, con il Segretario di Stato americano Anthony Blinken e Joseph Borrell schierati in sostegno del TPLF.

Un allineamento che non stupisce visto che molti dei vecchi amici dell’ex primo ministro etiope e uomo forte del TPLF Meles Zenawi sono entrati nell’entourage di Biden, dall’ex consigliera politica Susan Rice all’ambasciatrice all’ONU Linda Thomas Greenfield fino alla Direttrice di USAID Samantha Power. Per non parlare del numero uno dell’OMS Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, dirigente di lungo corso del TPLF.

In linea dunque con i propri storici rapporti con la dirigenza tigrina, gli USA hanno da subito guardato alla crisi in Tigray come ad una opportunità per poter riportare al potere i vecchi amici come aveva spiegato senza mezzi termini l’ex Vice Segretario di Stato americano per l’Africa Vicki Huddleston durante un meeting con il dirigente del TPLF Berhane Gebre Christos.

Le mancate promesse dell’uomo nuovo

Se dopo gli accordi di Pretoria i toni di Washington si ammorbidiscono, il feeling con gli USA non è certo paragonabile a quello di un tempo come è emerso lo scorso 30 novembre durante l’audizione della Commissione per gli Affari Esteri al parlamento americano: “Etiopia: promesse o pericoli, la situazione della politica americana”. Qui il deputato repubblicano John James non ha usato mezzi termini, spiegando come <<un’Etiopia stabile è utile al Corno d’Africa e un asset importante per portare avanti gli interessi strategici americani nella regione, tuttavia la direzione che sta prendendo l’Etiopia è preoccupante>>.

Per quanto l’Etiopia avrebbe tutto il diritto, ma evidentemente non la possibilità, di sganciarsi da Washington, è un fatto che la politica di Abiy si stia sempre più rivelando come autoritaria e inaffidabile. La decisione della Banca Africana di Sviluppo (AfDB) di lasciare l’Etiopia dopo la mancata promessa del Primo Ministro di effettuare un’indagine su un mancato trasferimento di 5,2 milioni di dollari (forse dirottati a Panama) e il conseguente arresto di due diplomatici in contravvenzione della Convenzione di Vienna, è solo l’ultimo caso di una leadership sempre più vulnerabile ad accuse di corruzione e dall’arresto facile, soprattutto nei confronti di giornalisti, attivisti e oppositori.

Dopo un inizio di belle promesse e dai toni panafricani, il governo di Abiy sta inoltre alimentando profonde divisioni etniche. La modifica alla Costituzione promessa nel 2018 non è mai arrivata e la specifica etnica è ancora nero su bianco sui documenti d’identità. Dopo aver accusato il TPLF di “tigrinizzare” del paese, Abiy Ahmed, di etnia oromo, sta a sua volta “oromizzando” i principali gangli del potere e in violazione della carta costituzionale, ha messo in piedi una guardia repubblicana di soli militari oromo che risponde direttamente al suo gabinetto.

Un leader dalla personalità narcisista che già a inizio mandato nel 2018 amava raccontare di come sua madre gli avesse predetto che sarebbe diventato il settimo re d’Etiopia, che ama sfoggiare un atteggiamento fatalista e provvidenziale tipico del movimento evangelico Prosperity Gospel cui Abiy, di fede protestante, sarebbe affiliato da tempo. Non a caso nominato dopo il passo indietro di Hailemariam Desalegn, anch’egli di fede protestante.

Una sorta di teologia del pensiero positivo che ha portato i fedelissimi a sostituire la parola “povertà” con “prosperità”. Un uomo “scollegato dalla realtà”, lo definiscono alcuni commentatori etiopi, che fornisce risposte laconiche a chi lo accusa di piantare alberi mentre in Etiopia si continua a morire: “serviranno a fare ombra a quanti riposano in pace”, e che nonostante un terzo dei bambini etiopi soffra di malnutrizione secondo l’indice 2020 HCI del capitale umano, e l’87 % della popolazione sia povero o prossimo alla povertà, ha pensato bene di costruirsi una residenza per un costo stimato di 10 miliardi di dollari, un decimo del prodotto interno lordo del paese.

Con quali soldi il premier inalbererà la sua reggia, è uno degli argomenti di discussione più tragicomici nei caffè della capitale. Se alcuni tirano in ballo i 2,6 miliardi di dollari sottratti alle casse dello stato dai suoi predecessori del TPLF (Fronte Popolare di Liberazione del Tigray), altri propendono per la stretta amicizia con gli Emirati Arabi Uniti da cui nelle ultime settimane, continuano ad arrivare aerei militari con misteriosi carichi.

Anziché portare pace e prosperità, come il nome del suo partito (Prosperity party) sembrava promettere, Abiy guida un paese dilaniato dalle guerre. Dopo quella in Tigray, da oltre un anno imperversano le violenze e discriminazioni contro l’etnia Amhara.

Una crisi che peraltro, in un triste gioco dell’assurdo, sembra avvicinare ulteriormente il TPLF alle istanze degli Oromo, in particolare a quelle dell’OLF (Oromo Liberation Front) e del suo braccio armato Oromo Liberation Army OLA). Entrambi i fronti etnici condividono infatti un atavico odio contro l’etnia Amhara percepita come dominante e oppressiva. E tutti accarezzano sogni di grandezza. (nelle foto qui sopra e sotto armi delle forze governative catturate in battaglia dalle milizie dell’OLA nelle recenti battaglie del novembre 2023).

Così come il TPLF, già nel suo manifesto del ’76, tratteggiava il miraggio di un “grande Tigray”, buona parte degli Oromo accarezza la visione di “una grande Oromia” o di un mitologico “Oromo empire of East Africa” che dovrebbe estendersi fino al Mar Rosso. Scenari tipici dell’ideologia Oromummaa che si ritiene preveda un’Etiopia oromiizata o, in alternativa, una repubblica Oromia indipendente motivo per cui la popolosa etnia amhara, 30 milioni di cui ben 15 vivono nella regione Oromo, è percepita come un ostacolo da eliminare.

I Fano: “la spina nel fianco” di Abiy

Proprio il fronte aperto con l’etnia Amhara ha rappresentato fino ad oggi il principale problema interno di Abiy alle prese con la difficile gestione di un Paese di 120 milioni di abitanti e 88 etnie. Una crisi iniziata lo scorso febbraio quando un gruppo di sacerdoti Oromo si era staccato dalla chiesa ortodossa etiope per fondare un proprio sinodo e così eseguire le proprie celebrazioni in lingua oromo. Una frattura poi rientrata ma che secondo gli Amhara sarebbe stata utilizzata dal premier per dividere la Chiesa e quindi il Paese.

A peggiorare le cose è arrivata poi la decisione del governo etiope di smantellare le forze militari speciali regionali. Nonostante l’apparente afflato nazionalista, l’iniziativa si declina da subito come un’operazione “ad personam”, diretta ad indebolire la resistenza Amhara, in particolare quella dei Fano, milizie volontarie nate negli anni ’30 contro l’occupazione italiana e che durante la crisi in Tigray si erano rivelate cruciali nel contenere l’avanzata del TPLF su Addis Abeba.

“Eroi nazionali” li aveva definiti allora il Primo Ministro che oggi invece li combatte. Al centro della resistenza Amhara la difesa delle terre di Welkait e Raya, storicamente amhara ma rivendicate dal TPLF come proprie al punto da chiamarle “Western Tigray”. Un termine controverso che gli Amhara non riconoscono

Il 4 agosto il premier proclama lo stato di emergenza nella regione Amhara arrogando a sé il potere di effettuare arresti senza mandato, imporre il coprifuoco, limitare i movimenti e vietare le riunioni pubbliche. Ne segue una escalation che ha esacerbato la guerra contro gli Amhara nel quasi totale silenzio mediatico.

Per quanto non siano organizzati in una unità centrale, grazie ad una perfetta conoscenza del territorio e alla possibilità di sorprendere l’esercito federale con imboscate, i Fano ad oggi hanno dato prova di grande forza sul campo e sono arrivati a controllare anche il 60% della regione Amhara. Una superiorità militare che ha portato l’esercito federale a ricorrere ad armi pesanti e a droni di provenienza turca. Non solo, proprio il 22 dicembre, un importante carico di armi sarebbe arrivato dalla Cina, in particolare fucili d’assalto AK 47 e AF56 oltre a ulteriori droni armati Wing Loong.

Una situazione di quasi guerra civile che rischia di deflagrare e che viene seguita attentamente oltreoceano. <<Mentre il governo di Abiy continua a guardare all’America per ricevere aiuti umanitari, l’Etiopia stringe legami più stretti con i concorrenti degli Stati Uniti come Cina, Emirati Arabi Uniti e Turchia, i contribuenti americani vogliono sapere dove vanno a finire i loro soldi>> ha ribadito ancora il deputato James.

Il “diritto” all’accesso al Mar Rosso

Con il Paese sempre più diviso e il fiato sul collo da parte degli USA, il tema dell’accesso sul Mar Rosso deve essere sembrato al premier etiope come un modo per risalire la china.

Il tema era stato portato all’attenzione dell’opinione pubblica con un’intervista registrata a giugno ma trasmessa sulla TV nazionale Fana solo lo scorso 13 ottobre. In quella occasione Abiy Ahmed aveva messo sul tavolo una vecchia questione, la necessità di avere uno sbocco al mare che per gli etiopi, tocca una ferita aperta, quella del porto “ceduto” all’Eritrea nel 1991 con l’indipendenza. Una ferita non ancora rimarginata nonostante l’accesso ai porti eritrei di Assab e Massawa non fosse mai stato precluso all’Etiopia. Fu anzi l’allora primo ministro etiope Meles Zenawi, durante il tentativo di occupare l’Eritrea nel 1998, a voler spostare le attività commerciali a Gibuti nella speranza di penalizzare economicamente il nemico.

Un obiettivo da raggiungere “con ogni mezzo possibile”, ha ribadito Abiy Ahmed (bella foto qui sopra) portando sulle difensive gli stati costieri Gibuti, Somalia ed Eritrea. Toni bellicosi che ricalcano il vecchio copione che investe il Corno d’Africa da oltre un secolo, lo stesso seguito dalla precedenti leadership etiopi, tutte contraddistinte da tentativi espansionistici nei confronti dell’Eritrea e permeabili alla solita logica del divide et impera molto cara oltreoceano.

Nonostante i pubblici auspici di stabilità, nei fatti gli USA hanno sempre dimostrato di voler mantenere il Corno d’Africa in un cronico stato di instabilità. L’aveva detto chiaramente nel 1951 l’Ambasciatore americano John Foster Dulles agli eritrei che chiedevano l’indipendenza. Nonostante “le opinioni del popolo eritreo devono essere prese in considerazione” spiegava, “l’interesse strategico degli Stati Uniti nel bacino del Mar Rosso e le considerazioni di sicurezza e di pace mondiale rendono necessario che il Paese (l’Eritrea) sia collegato con il nostro alleato Etiopia”.

Una posizione che secondo lo storico Theodore Vestal, sarebbe stata ribadita nel 1972 anche da Henry Kissinger che in un report confidenziale sottolineava come gli USA dovessero “mantenere l’Etiopia in un conflitto perenne e usare le divisioni etniche, religiose e di altro tipo per destabilizzare il Paese”. Raccomandazione cui l’alleanza con il TPLF, interessato a costituire un “grande Tigray” che inglobi parte della regione etiope Amhara nonché dello stato eritreo, è stata sempre funzionale.

Se non fosse per i toni poco diplomatici usati dal premier etiope, il tema avrebbe potuto essere oggetto di discussione costruttiva e trattativa economica con i Paesi confinanti.

Un’occasione di collaborazione interregionale necessaria in un continente dove solo il 15% dell’export è destinato ai paesi africani. Un modello che l’Etiopia peraltro, sta già cercando di portare avanti con la Diga sul Nilo Azzurro che fornisce energia elettrica a Sudan, Kenia e Gibuti.

Del resto, già nel 2018, l’accordo di pace con l’Eritrea, tratteggiava la possibilità per l’Etiopia di utilizzare i porti eritrei in regime tax free. Da allora però, nessun accordo è stato raggiunto e l’Etiopia continua ad appoggiarsi su Gibuti per un costo di quasi 2 miliardi di dollari all’anno. Una cifra enorme se si pensa che per le proprie basi navali nella ex colonia francese, USA e Cina non spendono più di 100 milioni di dollari. Non solo, il mancato sbocco sul mare ridurrebbe lo sviluppo dell’Etiopia di almeno il 20% rispetto al proprio potenziale a causa di un balzo dei costi di commercio e trasporto dal 50% al 262%.

Dopo le prime dichiarazioni tranchant, Abiy ha messo sul tavolo la possibilità di cedere quote dei principali asset del Paese come Ethio Telecom o Ethiopian Airlines in cambio dell’accesso al mare.

Le mire di Abiy: spunto per un’altra guerra?

“Un pazzo”. Hanno commentato alti ufficiali della Somalia ribadendo come “sacrosanta” la propria integrità territoriale. Più compassata invece la risposta del Ministro dell’Informazione eritreo che ha invitato a non cedere a provocazioni. Dietro i toni asciutti degli eritrei, tutto però lascia pensare che dopo le strette di mano profuse ai media durante la pace, oggi Eritrea ed Etiopia siano ormai molto distanti, anche come proiezione internazionale.

Mentre l’Etiopia sembra voler alimentare le tensioni interne ed esterne, per Isaias Afewerki e i suoi 30 anni di guida ininterrotta dell’Eritrea, il 2023 è stato l’anno di una fine tessitura diplomatica. Dopo essere stato ricevuto con tutti gli onori a Pechino, a Mosca, e al summit dei Brics in Sud Africa, anche a quello Arabia-Africa di Riad dello scorso novembre, il presidente Afewerki non ha perso occasione per rimarcare la distanza da Addis Abeba intrattenendo almeno il triplo degli incontri rispetto al premier etiope.

Mentre quest’ultimo continuava ad alimentare lo spettro della guerra tratteggiando l’antico regno di Axum che dalle terre dell’Etiopia si estendeva all’Arabia abbracciando il Mar Rosso, Afewerki preferiva rimarcare la necessità di aumentare la cooperazione tra paesi africani in nome della stabilità regionale e della pace. Proprio la sicurezza del Mar Rosso è stata al centro dell’incontro con il Presidente egiziano Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, uno dei primi antagonisti della politica di Abiy.

A rendere ancora più profonda la distanza tra i leader eritreo ed etiope, sono state inoltre le accuse rivolte da quest’ultimo all’Eritrea, ritenuta responsabile di aiutare militarmente la resistenza Amhara e frange di quella Oromo che comunque stanno dando del filo da torcere ad Abiy per indebolirlo ulteriormente. Un atteggiamento percepito dall’Eritrea come ingrato, visto l’aiuto di quest’ultima in Tigray, nonché pretestuoso dato che ad oggi non vi sono prove di aiuti militari (politici forse) da parte dell’Eritrea, contrariamente invece alla presenza dell’esercito federale etiope nelle terre Amhara che rende quasi impossibile per l’Eritrea fornire supporto ai Fano.

La questione del porto rappresenta dunque l’ennesimo elemento di frattura tra Eritrea ed Etiopia e sibilline in questo contesto suonano le parole di Seyoum Teshome, membro del partito di Abiy Ahmed. A detta del politico, un nuovo conflitto sarebbe imminente e potrebbe iniziare con un’operazione sotto falsa bandiera del Tigray diretta a provocare l’Eritrea. Se a quel punto, l’Eritrea dovesse iniziare la guerra, Abiy potrebbe sfruttare questa opportunità per prendere il controllo del porto eritreo di Assab.

Uno scenario che potrebbe essere facilitato anche dalle diverse posizioni di Etiopia ed Eritrea rispetto alle fazioni che si contendono il Sudan e che l’avanzata delle RSF (Rapid Support Force) verso Sud potrebbe complicare. In quest’ottica, accusare preventivamente il governo eritreo per “interferenze” in Etiopia o in Sudan, potrebbe rimettere sul tavolo gli antichi piani di regime change in Eritrea, garantendo all’Etiopia il sostegno finanziario dell’Occidente e quella legittimità di leader che ultimamente Abiy sembra aver perduto.

Una nuova guerra sarebbe anche l’occasione per portare avanti quanto richiesto dai ribelli tigrini nonché dai report della Commissione delle Nazioni Unite sui diritti umani e dal Dipartimento di Stato americano e quindi consegnare ai tigrini il cosiddetto “Western Tigray”.

Un punto sul quale Abiy sta ricevendo non poche pressioni. Non è un caso infatti che nonostante questa dicitura sia contestata dagli Amhara e buona parte degli etiopi, sui tavoli internazionali si parli sempre di “Western Tigray”. Anche quando Mike Hammer, durante l’audizione della Commissione per gli Affari Esteri al parlamento americano, cercava rassicurava i deputati USA sulle intenzioni non bellicose di Abiy, il democratico Brad Sherman, da sempre grande portavoce delle istanze tigrine, ribadiva la necessità di concedere i fondi del Fondo Monetario Internazionale (IMF) all’Etiopia solo dopo la soluzione del “Western Tigray”.

Un linguaggio che la dice lunga su quanto il Tigray sia importante per le manovre politiche di Washington nella regione. Non a caso, ancora oggi, il tema della “fame in Tigray” continua ad oscurare altre emergenze come le violenze a danno degli Amhara e a tenere banco sui tavoli internazionali. Gli ex ribelli tigrini lo sanno bene, come dimostra l’ultimo comunicato di Getachew Reda che è tornato ad accusare Addis Abeba di non fare abbastanza per la fame che affliggerebbe la regione.

I segni di complicità tra Washington e la leadership etiope non mancano. Non ultima la scelta da parte dell’ambasciata americana ad Addis Abeba di definire la capitale etiope “Finfiné”, un termine controverso ma molto caro agli estremisti Oromo.

Giochi di equilibrismo anche per Abiy che oltre che della Cina (che a differenza degli USA ha recentemente annullato il debito etiope), degli Emirati Arabi Uniti che continuano a rifornire le esangui casse etiopi di valuta estera e a rimpolpare l’esercito federale di armi, non può certo permettersi di fare a meno degli Stati Uniti. Questi, dalla loro, sembrano consapevoli di come in questo momento di grande instabilità nella regione, l’Eritrea possa essere determinante per gli equilibri del Corno d’Africa.

L’apertura suggerita dal comunicato del 12 novembre è però durata poco. Solo dopo alcuni giorni, gli USA sono tornati al solito registro di accuse contro Asmara, ritenuta responsabile di non aver ancora ritirato le proprie truppe dal Tigray e di interferire con gli affari interni del Sudan.

Di certo, prendere di mira l’Eritrea in questo momento non sembra la mossa migliore per permettere ad Etiopia e Stati Uniti di riposizionarsi nell’area. Mai come ora infatti, in un continente che dopo sette colpi di stato susseguitisi nell’Africa centrale, si mostra sempre più insofferente alle ingerenze occidentali, l’Eritrea gode di un’ottima reputazione anche per una questione simbolica, quella di unico paese africano indipendente da meccanismi di controllo esterni o basi militari straniere. Non a caso, quando lo scorso luglio il Consiglio sui diritti umani delle Nazioni Unite si è riunito per rinnovare il mandato allo special rapporteur per l’Eritrea, questo non è stato votato da neanche uno stato africano.

L’accordo col Somaliland

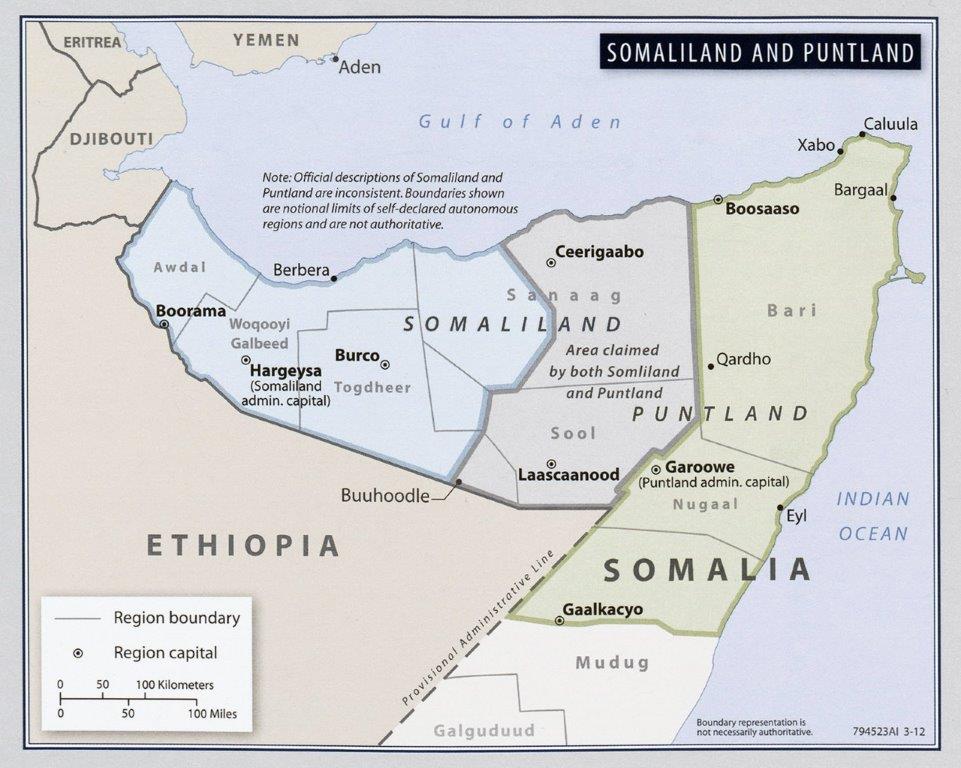

Una parziale distensione con Gibuti e l’Eritrea potrebbe venire determinata dall’intesa tra Etiopia e Somaliland (l’ex Somalia Britannica) annunciata ieri: l’agenzia Bloomberg ha reso noto che Addis Abeba ha firmato un memorandum d’intesa con il Somaliland, regione separatista della Somalia settentrionale di fattoi autonoma dal 1991 ma non riconosciuta dalla comunità internazionale, per ottenere l’accesso al Mar Rosso in cambio di una partecipazione azionaria nella compagnia di bandiera Ethiopian Airlines.

I negoziati dettagliati per raggiungere un accordo formale saranno conclusi entro un mese, ha affermato Redwan Hussein, consigliere per la sicurezza nazionale del primo ministro Abiy Ahmed. Non ha rivelato la quota che l’Etiopia offrirà della più grande compagnia aerea africana.

Il protocollo d’intesa consentirà all’Etiopia di accedere al Mar Rosso dal Somaliland per utilizzarlo come base militare e per scopi commerciali per 50 anni, ha detto Hussein in un briefing lunedì nella capitale Addis Abeba. Sarà in grado di affittare un “accesso lungo 20 chilometri (12 miglia) per la base della Marina Etiope e di essere utilizzato come uno dei suoi porti di ingresso”, ha detto il presidente del Somaliland Muse Bihi Abdi.

Notizia che di fatto anticipa la ricostituzione di una Marina Etiope (a lato il suo stemma), che di fatto cessò di esistere nel 1991 con l’indipendenza dell’Eritrea ed è stata ufficialmente disciolta nel 1996.

In base all’intesa con il Somaliland, l’Etiopia potrà anche costruire infrastrutture e un corridoio terrestre tra il territorio etiope e il porto, probabilmente quello di Berbera già collegato al territorio etiopico da una importante arteria stradale che nelle intenzioni etiopiche dovrebbe venire presto affiancata da una linea ferroviaria.

Sul piano politico l’accordo prevede che l’Etiopia riconosca il Somaliland come stato sovrano, ha affermato Bihi Abdi; un passo importante affinché in prospettiva lo stato somalo con capitale Hargeisa possa venire riconosciuto anche da altre nazioni e dall’Unione Africana.

“L’accordo firmato costituisce una seria preoccupazione per la Somalia e per l’intera Africa. Il rispetto della sovranità e dell’integrità territoriale è il fondamento della stabilità regionale e della cooperazione bilaterale. Il governo somalo deve rispondere in modo appropriato” ha detto l’ex presidente somalo Mohamed Farmaajo in un tweet di fuoco.

Il 29 dicembre erano ripresi a Gibuti i colloqui fra il presidente somalo Hassan Sheikh Mohamud e il presidente del Somaliland, che dal 1991 rivendicano l’indipendenza dal Paese. Lo ha riferito il sito riferisce “Garowe online” ripreso in Italia da Agenzia Nova.

Il dialogo si era interrotto alcuni mesi fa dopo che le parti non sono riuscite a concordare i termini di un’intesa che porti al riconoscimento dell’ex Somalia Britannica.

Foto: Presidenza Etiopica, Agenzia Nova, Forze Armate Etiopiche, OLA, TPLF, EIA, Marina Etiopica e Library Texas University

ENGLISH EDITION

After almost two decades of amnesia, last December 12, on the 23rd anniversary of the Algiers agreements, the US State Department wrote a 6-line statement to reiterate the importance of respecting the Ethiopia – Eritrea borders.

A “curious” note given that Ethiopia had not respected the agreement for almost 18 years. A long period of time during which, the US never had anything to object to.

Apparently, the official not can be seen as a sign of openness to Eritrea which for immemorial time has been one of the favorite targets of “humanitarian concerns” and American sanctions. At the same time, it’s a warning to Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed who, with his latest statements on Ethiopia’s right to have an access to the Red Sea, has alerted the neighbouring countries, starting with Eritrea.

For Joe Biden’s administration it is not a conversion on the road to Damascus, nor a simple ritual homage as confirmed by the sudden copy-paste of the secretariat of the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Joseph Borrell. After all, the current American foreign policy follows the footsteps of previous administrations which have always silently supported the Ethiopian occupation of the Eritrean borders in the Badme area. A total failure to comply with the Algiers agreements of 2000 and the directives of the Ethiopian Boundary Commission of the United Nations, carried out in the general disinterest of the international community which ended only in 2018 with the arrival of Abiy Ahmed who withdrew the Ethiopian troops from the area and eased the relations with Eritrea. A set of moves that led him to the Nobel Peace Prize.

Evidently, to review their African strategy Americans needed the Houthis, the Shiite rebels from Yemen who have been threatening ships on the Red Sea for weeks.

Moreover, the Bab al-Mandab Strait is of extreme interest, 12% of world trade flows through it, 10% of oil delivered by sea and 8% of gas (LNG). Supplies to Israel also pass from here and the expansion of a southern front of the conflict in Gaza highlights in all its problematic nature the ever-increasing isolation in the area of both Israel and the USA which see their historic allies as Egypt and Arabia Saudi Arabia increasingly closer to the Chinese sphere of influence and the BRICS.

In this scenario, an escalation in the Middle East, in addition to destabilizing the Arabian peninsula, could be an excellent opportunity to undermine the Shiite-Sunni peace agreement brokered by China, bring the Saudis back under Washington’s influence and thus relaunch the Abraham accords.

In fact, it is no mystery that the weakening of the BRICS and its two fundamental countries (Russia and China) are seen by the US as the fundamental element of their foreign policy and from this perspective, a new dialogue with Eritrea could certainly be useful, starting from an involvement in the international police operations Prosperity Guard (OPG). Furthermore, in addition to being the central hub of the Silk Road, with its 1,251 kilometers of coast on the Red Sea, Eritrea is the first neighbor of Yemen and, thanks to its excellent relations with Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Sudan, could prove crucial for the balances of the area.

On the other hand, Ethiopia, a historic US outpost in East Africa, is turning out to be a Country whose current political structure, not to mention its entrance in the BRICS, does not seem to completely convince Washington, as uninterested as it is in saving the African country from the economic abyss, starting from those 3.5 billion dollars from the International Monetary Fund and also the World Bank to which Ethiopia is still burdened. With a reduction of 30% and a serious lack of foreign currency, Ethiopia is facing a very difficult economic situation, so much so that after the failure to pay a 33 million dollar coupon on a 1 billion dollar bond issued in 2014 , is now officially in default. The third African country after Zambia and Ghana to collapse on its foreign debt.

Ethiopia-USA: back to their old fling?

Until a few months ago, everything suggested that Ethiopia and the United States had rediscovered their historical liaison, the one built during the 27 years in which the TPLF (Tigray People’s Liberation Front) was in power and in which Ethiopia became a sort of satellite state of Washington, a precious outpost in a strategic area like the Horn of Africa.

A complicity interrupted in 2018 when Abiy Ahmed’s first moves suggested a new course of clear independence from the American interests.

Not only for the decision to ease relations with Eritrea, in contrast with US and their policy of accusing Eritrea, among other things, of supporting the Somali terrorists of Al Shabaab only to later admit that it had never had proof, but also for the decision to carry out the construction of the Grand Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile, again in full contrast with the US, fully aligned with Egypt and therefore quite busy in amplifying Cairo’s concerns on water management.

In the beginning, Abiy showed his preference for national interests over overseas pressure also during the war in Tigray. A crisis triggered by the TPLF on November 4, 2020 against the Ethiopian government which was narrated by international media as a genocide carried out by Abiy Ahmed against the Tigrayans ethnic group. Actually, there was no genocide, no blockade of aid as witnessed also by the World Food Program whose convoys reached 3 million people in 2022 alone. Instead, there was a secession war unleashed by the Tigrayan armed group against the army federal government and the neighboring Amhara and Afar regions, which resulted in a series of war crimes committed by both sides and paid, primarily, by Ethiopia, promptly sanctioned by the USA with the suspension of the export facilitations provided by Agoa (African Growth and Opportunity Act) for “humanitarian reasons”. Facilities which had allowed Ethiopian exports to the USA to grow by over 50% in a year but which, once suspended, caused the loss of at least 100 thousand jobs.

Then something changed. Abiy Ahmed has changed (consensus has dramatically dropped) and after the recent war in Tigray, also the international community’s attitude towards Ethiopia have changed (“curiously” for the better). A transformation that has its turning point in the peace agreement that signed in Pretoria on 2 November 2022 by the Ethiopian government and TPLF, which ended the conflict with a toll of one million deaths and 25 billion dollars of expenses.

An enormous damage caused by the war which earned the TPLF the designation of a “terrorist group” by the Ethiopian parliament, only to remove that after the peace agreements. However, not all points of the agreement have been respected and to date, the disarmament of the TPLF has not been completed yet. Despite the internal divisions, TPLF is still militarily strong and can count on 200 thousand armed men, their leaders also still firmly in place. From Debretsion Gebremichael to former spokesperson Getachew Reda who leads the interim government of Tigray and does not mind shaking hands with Ethiopian Prime Minister whom only 12 months ago he was to call a “genocidal and bloody leader”.

This constant approach to TPLF by the Ethiopian prime minister is perceived as a betrayal by almost the entire population, which remembers very well how the former leadership used to guide the Country with an iron fist, driving bloody repressions of the Oromo and Amhara protests in 2015 and 2016 and waging a war against Eritrea in 1998.

A sense of betrayal also pervades those who were part of #nomore, the “African pride” movement which during the Tigray conflicted looked at Abiy as a symbol of resistance against Western interference. At that time, Ethiopia was the victim of a heavy media campaign, with US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken and EU representative Joseph Borrell fully supporting the TPLF. An alignment that is no surprise considering how many of the former Ethiopian prime minister Meles Zenawi old friends, have taken part to Biden’s entourage, from former political advisor Susan Rice to UN ambassador Linda Thomas Greenfield up to USAID Director Samantha Power. Not to mention WHO number one Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, long-time leader of the TPLF.

Therefore, following their historical relations with the Tigrayan leadership, US have immediately looked at the crisis in Tigray as an opportunity to bring their old friends back to power as the former US Deputy Secretary of State had explained bluntly for Africa Vicki Huddleston during a meeting with TPLF leader Berhane Gebre Christos.

The “new man” already “old”

If after the Pretoria agreements Washington’s attitude towards Ethiopia softens for a while, the current relation is certainly not comparable to the olden days. The cracks emerged last November 30 during the hearing of the Foreign Affairs Committee in the American parliament: “Ethiopia: promises or dangers, the state of American politics”. There, the Republican congressman John James explained how <<a stable Ethiopia is useful to the Horn of Africa and an important asset for advancing American strategic interests in the region. However – he added – the direction Ethiopia is taking is worrying>>.

Although Ethiopia would have every right, but evidently not the possibility, to disengage from Washington, it is a fact that Abiy’s policy is increasingly revealing itself to be authoritarian and unreliable. The decision of the African Development Bank (AfDB) to leave Ethiopia after the Prime Minister’s failure to promise to carry out an investigation into a failed transfer of 5.2 million dollars (perhaps diverted to Panama) and the subsequent arrest of two diplomats in contravention of the Vienna Convention, is only the latest case of a leadership increasingly vulnerable to accusations of corruption and easy arrest, especially towards journalists, activists and opponents.

After a start full of beautiful promises and pan-African wishes, Abiy’s government found itself fueling deep ethnic divisions. The change to the Constitution promised in 2018 has never arrived and the ethnic specification is still black and white on identity documents. After accusing the TPLF of “Tigrinizing” the Country, Abiy Ahmed, of the Oromo ethnic group, is in turn “Oromosing” the main centers of power and in violation of the constitutional charter, has set up a republican guard of only Oromo soldiers who reports directly to his cabinet.

He is a leader perceived to have a narcissistic personality who could be easily perceived when at the beginning of his mandate in 2018, he loved to tell how his mother had predicted to him that he would become the seventh king of Ethiopia. A man who loves to show off a fatalistic and providential attitude typical of the evangelical movement Prosperity Gospel which Abiy, an Oromo of Protestant faith, have been affiliated for some time. It is no coincidence that he was appointed after the Hailemariam Desalegn, also of the Protestant faith, resigned.

A sort of theology of positive thinking that has led him to replace the word “poverty” with “prosperity” and to stuff his speeches with concepts such as “medemer”, which he also reiterated in his Nobel acceptance speech.

To some Ethiopian commentators Abiy is a man “disconnected from reality” who provides laconic answers to those who accuse him of planting trees while people continue to die in Ethiopia: “they will serve to shade those who rest in peace”, and who despite a third of Ethiopian children suffer from malnutrition according to the 2020 HCI human capital index, and 87% of the population is poor or close to poverty, is building a 10 billion dollars palace, a tenth of gross domestic product of the Country.

With what money the Prime Minister will build his palace, is one of the most tragicomic topics of discussion in Addis Abeba cafés. While some refer to the 2.6 billion dollars stolen from the state coffers by his TPLF predecessors, others call the the close friendship with the United Arab Emirates as in recent weeks, military planes with mysterious cargoes keep arriving from there.

Instead of bringing peace and prosperity, as the name of his party (Prosperity Party) seemed to promise, Abiy leads a Country torn by wars. After the one in Tigray, violence and discrimination against the Amhara ethnic group have been raging for over a year.

A crisis which, moreover, in a sad game of the absurd, seems to bring the TPLF further closer to the Oromo demands, in particular those of the OLF (Oromo Liberation Front) and its armed wing OLA (Oromo Liberation Army). In fact, both ethnic fronts share an atavistic hatred against the Amhara ethnic group perceived as dominant and oppressive. Both also cherishes “big dreams”: as the TPLF, in its ’76 manifesto, outlined the mirage of a “great Tigray”, a good part of the Oromo still cherish the vision of “a great Oromia” or of a mythological “Oromo empire of East Africa” which should extend up to the Red Sea. Typical scenarios of the Oromummaa ideology which is believed to envisage an Oromized Ethiopia or, alternatively, an independent Oromia republic which is why the populous Amhara ethnic group, 30 million of which 15 million live in the Oromo region, is perceived as an obstacle to be eliminated.

Fano: Abiy’s nightmare

The open front with the Amhara group has so far represented Abiy’s main internal problem as he deals with the difficult management of a country of 120 million inhabitants and 88 ethnic groups. A crisis that began last February when a group of Oromo priests wanted to separate from the Ethiopian Orthodox Church to found their own synod and thus perform their own celebrations in Oromo language. A fracture that later was solved but which according to the Amhara was used by the Prime Minister to divide the Church and therefore the Country.

To make matters worse, came the Ethiopian government’s decision to dismantle the regional special military forces. Despite the apparent nationalist inspiration, the initiative was immediately seen as an “ad personam” operation, aimed at weakening the Amhara resistance, in particular that of the Fano, voluntary militias born in the 1930s against the Italian occupation and which during the crisis in Tigray were crucial in containing the TPLF’s advance on Addis Ababa. While Abiy once defined them as “national heroes”, today he is fighting them. At the center of the Amhara resistance is the defense of Welkait and Raya, historically Amhara but claimed by the TPLF as theirs to the point of calling them “Western Tigray”. A controversial term that the Amhara do not recognize

On August 4, the Prime Minister proclaimed a state of emergency in the Amhara region, arrogating to himself the power to make arrests without a warrant, impose a curfew, limit movements and ban public gatherings. A decision that exacerbated the war against the Amhara even if surrounded by almost total silence from the media

Although they are not organized into a central unit, thanks to a perfect knowledge of the territory and the possibility of surprising the federal army with ambushes, the Fano have to date shown great strength in the field and have managed to control up to 60% of the Amhara region. A military superiority that led the federal army to resort to heavy weapons and drones of Turkish origin. Not only that, on December 22, a significant shipment of weapons arrived from China, in particular AK 47 and AF56 assault rifles, plus Wind Loong JG1 drones.

A situation of almost civil war that risks to get worse day by day and which is being carefully followed overseas. <<As Abiy’s government continues to look to America for humanitarian aid, Ethiopia forges closer ties with US competitors such as China, the United Arab Emirates and Turkey, American taxpayers want to know where the their money>> congressman James reiterated again.

“The right” to the sea

With Ethiopia increasingly divided and the US breathing down its neck, the issue of an “access to the Red Sea” must have seemed to the Ethiopian prime minister like a way to get back on top.

The topic was brought to the attention of public opinion with an interview recorded in June but broadcast on national TV Fana only last October 13th. On that occasion Abiy Ahmed had put an old issue on the table, the need to have an access to the sea which for Ethiopians touches an open wound, that of the port “given” to Eritrea in 1991 along with the independence. A wound that has not yet healed even the access to the Eritrean ports of Assab and Massawa was never been denied to Ethiopia. Indeed, it was the then Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, during the attempt to occupy Eritrea in 1998, who wanted to move commercial activities to Djibouti in the hope of economically penalizing the enemy.

An objective to be achieved “by any means possible”, has later reiterated Abiy Ahmed, bringing the coastal states Djibouti, Somalia and Eritrea onto the defensive. Warlike tones typical of the usual script that has been impressed on the Horn of Africa for over a century, the same followed by the previous Ethiopian leadership, all characterized by expansionist attempts towards Eritrea and permeable to the usual logic of divide and conquer, very much liked overseas.

Despite public hopes for stability, in reality the US has always demonstrated their desire to keep the Horn of Africa in a chronic state of instability. The American Ambassador Joh Foster Dulles had said it clearly in 1951 to the Eritreans who were asking for independence. Although “the opinions of the Eritrean people must be taken into consideration,” he explained, “the strategic interest of the United States in the Red Sea basin and considerations of security and world peace make it necessary for the country (Eritrea) to be connected with our ally Ethiopia”. A position which, according to the historian Theodore Vestal, was also reiterated in 1972 by Henry Kissinger who in a confidential report underlined how the USA had to “keep Ethiopia in a perennial conflict and use ethnic, religious and other divisions to destabilize the country”. A recommendation for which the alliance with the TPLF, interested in establishing a “great Tigray” that includes part of the Ethiopian Amhara region as well as the Eritrean state, has always been functional.

If it were not for the undiplomatic tones used by the Ethiopian Prime Minister, the issue could have been the subject of constructive discussion and economic negotiation with neighboring countries.

An opportunity for interregional collaboration much needed in a continent where only 15% of exports are destined for African countries. A model that Ethiopia is already trying to carry forward with the Blue Nile Dam which supplies electricity to Sudan, Kenya and Djibouti. It is no coincidence that, after the first forceful declarations, Abiy put on the table the possibility of selling shares in the Country’s main assets such as Ethio Telecom or Ethiopian Airlines.

Moreover, already in 2018, the peace agreement with Eritrea outlined the possibility for Ethiopia to use Eritrean ports under a tax free regime. Since then, however, no agreement has been reached and Ethiopia continues to rely on Djibouti at a cost of almost 2 billion dollars a year. An enormous amount of money if we consider that the USA and China do not spend more than 100 million dollars on their naval bases. Not only that, the lack of access to the sea would reduce Ethiopia’s development by at least 20% compared to its potential due to a jump in trade and transport costs from 50% to 262%.

Abiy’s aims: the excuse for another war?

“A madman”. High officials from Somalia commented, reiterating their territorial integrity as “inviolable”. The response of the Eritrean Minister of Information, however, was more staid and urged not to give in to provocations. Behind the dry tones of the Eritreans, however, everything suggests that after the many handshakes offered to the media during the 2018 peace, today Eritrea and Ethiopia are very distant, also on their international projection.

While Ethiopia keeps fueling internal and external tensions, for Isaias Afewerki and his 30 years of uninterrupted leadership of Eritrea, 2023 was the year of a fine diplomatic weaving. After being received with full honors in Beijing, Moscow, and at the Brics summit in South Africa, including at the Arabia-Africa summit in Riyad last November, Afewerki did not miss an opportunity to underline the distance from Addis Ababa by entertaining at least three times as many meetings as the Ethiopian Prime Minister. While Abiy latter continued to fuel the specter of war by outlining the ancient kingdom of Axum which extended from the lands of Ethiopia to Arabia embracing the Red Sea, Isaias preferred to underline the need to increase cooperation between African countries in the name of stability regional and peace. The security of the Red Sea was precisely at the center of the meeting with Egyptian President Al Sisi, one of the main antagonists of Abiy’s policy.

What further deepened the distance between the Eritrean and Ethiopian leaders were the accusations leveled by the latter against Eritrea, held responsible for militarily helping the Amhara resistance and fringes of the Oromo resistance which are however giving a hard time to Abiy as they are weakening him further. An attitude perceived by Eritrea as ungrateful, given their help in Tigray’s war and given that to date there is no evidence of military aid (political perhaps) from Eritrea, while the Ethiopian federal army in the Amhara lands’ presence makes it almost impossible for Eritrea to provide support to the Fano.

The port issue therefore represents yet another element of fracture between Eritrea and Ethiopia and in this context the words of Seyoum Teshome, a member of Abiy Ahmed’s party, sound cryptic. According to the politician, a new conflict is imminent and could begin with a false flag operation by Tigray aimed at provoking Eritrea. If at that point, Eritrea were to start war, Abiy could use this opportunity to take control of the Eritrean port of Assab.

A scenario that could also be facilitated by the different positions of Ethiopia and Eritrea towards to the factions competing for Sudan and which the advance of the RSF (Rapid Support Force) towards the South could complicate.

From this perspective, blaming Isaias’s government in advance for “interferences” in Ethiopia or Sudan could put the old regime change plans in Eritrea back on the table, guarantee the financial support of the West and that legitimacy that Abiy deeply needs.

A new war would also be an opportunity to satisfy the Tigrayan rebels requests on “Western Tigray”as it is stressed in the United Nations Commission on Human Rights and the US State Department reports. An issue on which Abiy is without a doubt receiving a lot of pressure. It is no coincidence in fact that although this term is contested by the Amhara and a large part of the Ethiopians, on international tables there is always talk of “Western Tigray”. Even when Mike Hammer, during the hearing of the Foreign Affairs Committee in the American parliament, tried to reassure the US deputies about Abiy’s non-warlike intentions, the Democrat Brad Sherman, always a great spokesperson for the Tigrayan demands, reiterated the need to grant the funds from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to Ethiopia only after the “Western Tigray” solution. A language that tells a lot about how important Tigray is for Washington’s political maneuvers in the region. It is no coincidence that, even today, the topic of “hunger in Tigray” continues to overshadow other emergencies such as the violence against the Amhara and to hold sway on international tables. The former Tigrayan rebels know this well as demonstrated by the latest statement from Getachew Reda who has once again has accused Addis Ababa of not doing enough to address the hunger that would afflict the region.

The carrot and the stick old strategy, we could say, given that, when necessary, Washington shows off its complicity with the Ethiopian leadership. Last but not least, the choice by the American embassy in Addis Ababa to define the Ethiopian capital as “Finfiné”, a controversial term but very dear to Oromo extremists.

Balancing games also for Abiy who needs China (which unlike the US has recently canceled Ethiopia’s debt), the United Arab Emirates which continues to replenish the bloodless Ethiopian pockets with foreign currency while replenishing the federal army with weapons, and who can’t certainly afford to stay without the United States. Overseas thought, they seem pretty aware of how in this moment of great instability in the region, Eritrea can be more decisive than Ethiopia for the balance of the Horn of Africa.

However, the opening suggested by the November 12 statement did not last long. Only after a few days, the USA returned to the usual register of accusations against Asmara, held responsible for not having yet withdrawn its troops from Tigray and for interfering with Sudan’s internal affairs.

Certainly, targeting Eritrea at this time does not seem like the best move to allow Ethiopia and the United States to place themselves back in the area. At this time Eritrea can count on an excellent reputation in the “global south” also for a symbolic reason, since it is the only African country independent from external control mechanisms or military bases of some kind. It is no coincidence that last July, when the United Nations Human Rights Council met to renew the mandate of the special rapporteur for Eritrea, this was not voted on by even one African state.

The deal with Somaliland

A partial easing with Djibouti and Eritrea could be determined by the agreement between Ethiopia and Somaliland (the former British Somalia) announced the first of January: Addis Ababa has signed a memorandum of understanding with Somaliland, separatist region of northern Somalia, de facto autonomous since 1991 but not recognized by the international community, to obtain access to the Red Sea in exchange for a shareholding in the national airline Ethiopian Airlines.

Detailed negotiations to reach a formal agreement will be concluded within a month, said Redwan Hussein, national security adviser to Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. He did not disclose the share Ethiopia will offer of Africa’s largest airline.

The memorandum of understanding will allow Ethiopia to access the Red Sea from Somaliland for use as a military base and for commercial purposes for 50 years, Hussein added and it will be able to lease a “20-kilometer (12-mile) long access to the Ethiopian Navy base and be used as one of its ports of entry” as Somaliland President Muse Bihi Abdi said.

News which in fact anticipates the reconstitution of an Ethiopian Navy (its coat of arms next to it), which effectively ceased to exist in 1991 with the independence of Eritrea and was officially dissolved in 1996.

Based on the agreement with Somaliland, Ethiopia will also be able to build infrastructures and a land corridor between Ethiopian territory and the port, probably that of Berbera, already connected to Ethiopian territory by an important road artery which in Ethiopian intentions should soon be joined from a railway line.

On a political level, the agreement precondition is for Ethiopia to recognize Somaliland as a sovereign state: an important step as pointed out by the Somaliland President so that in the future can also be recognized by other nations and by the African Union.

“The signed agreement constitutes a serious concern for Somalia and for the whole of Africa. Respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity is the foundation of regional stability and bilateral cooperation. The Somali government must respond appropriately,” said former Somali president Mohamed Farmaajo in a fiery post on X.

On December 29, talks resumed in Djibouti between Somali president Hassan Sheikh Mohamud and the president of Somaliland, which has been claiming independence from the Country since 1991. This was reported by the site “Garowe online” reported in Italy by Agenzia Nova.

The dialogue was interrupted a few months ago after the parties failed to agree on the terms of an agreement leading to the recognition of the former British Somalia.

Francesca RonchinVedi tutti gli articoli

Giornalista RAI (Agorà, Porta a Porta, Report) e La7. Ha scritto per il Corriere.it e Il Fatto Quotidiano. Oggi collabora con Panorama. Negli ultimi anni si è specializzata sul tema dell'immigrazione, approfondendo in particolare le dinamiche legate al flusso migratorio proveniente dal Corno d'Africa e realizzando reportage tra Italia, Macedonia, Polonia, Etiopia, Eritrea e al largo delle coste libiche. Un viaggio sulla nave della ONG sos Méditerranée, per un servizio andato in onda a Report, ha dato spunto al libro "IpocriSea, le verità nascoste dietro i luoghi comuni su immigrazione ONG".